MAKE A MEME

View Large Image

| View Original: | RobertCotton1626.jpg (494x596) | |||

| Download: | Original | Medium | Small | Thumb |

| Courtesy of: | commons.wikimedia.org | More Like This | ||

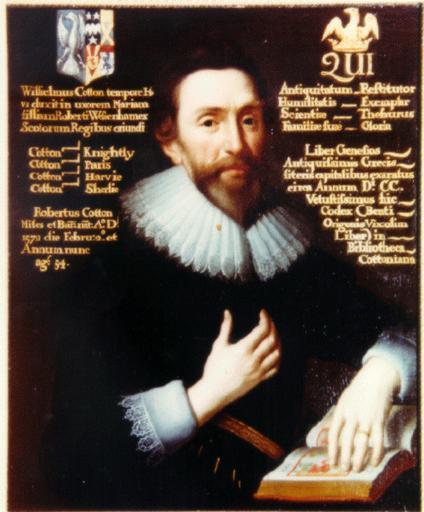

| Keywords: people Sir Robert Bruce Cotton, 1st Baronet (22 January 1570/1 – 6 May 1631) was an English politician, founder of the famous Cotton library. He was of a Huntingdonshire parentage and educated at Westminster School, where he became interested in antiquarian studies under William Camden, and Jesus College, Cambridge (B.A. 1585).[1] Starting with his antiquarian notes on the local history of Huntingdonshire, he began to amass a library, in which the documents rivalled, then surpassed the official Public Record Office collections. He entered the Parliament of England as a member for Huntingdon in 1601. He helped devise the institution of the title baronet as a means for King James I of England to raise funds. Despite his early period of goodwill with James I, during which he was made a baronet, Cotton's politics, based on his immersion in the documents, was essentially that "sacred obligation of the king to put his trust in parliaments" expressed in his published The Dangers wherein the Kingdom now standeth, and the Remedye (1628), which from the Court party's point-of-view was anti-royalist in nature; the authorities began to fear the uses being made of his library to support parliamentarian arguments: it was confiscated in 1630 and returned only after his death to his heirs. The Cottonian Library was the richest private collection of manuscripts ever amassed; of secular libraries it outranked the Royal library, the collections of the Inns of Court and the College of Arms; Cotton's house near the Palace of Westminster became the meeting-place of the Society of Antiquaries and of all the eminent scholars of England (DNB); it was eventually donated to the nation by Cotton's grandson and now resides at the British Library. The physical arrangement of Cotton's Library continues to be reflected in citations to manuscripts once in his possession. His library was housed in a room 26 feet (7.9 m) long by six feet wide filled with bookpresses, each with the bust of a figure from classical antiquity on top. Counterclockwise, these are catalogued as Julius (i.e., Julius Caesar), Augustus, Cleopatra, Faustina, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, Nero, Galba, Otho, Vitellius, Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian. (Domitian had only one shelf, perhaps because it was over the door.) Manuscripts are now designated by library, bookpress, and number: for example, the manuscript of Beowulf is designated Cotton Vitellius A.xv, and the manuscript of Pearl is Cotton Nero A.x. Sir Robert Bruce Cotton, 1st Baronet (22 January 1570/1 – 6 May 1631) was an English politician, founder of the famous Cotton library. He was of a Huntingdonshire parentage and educated at Westminster School, where he became interested in antiquarian studies under William Camden, and Jesus College, Cambridge (B.A. 1585).[1] Starting with his antiquarian notes on the local history of Huntingdonshire, he began to amass a library, in which the documents rivalled, then surpassed the official Public Record Office collections. He entered the Parliament of England as a member for Huntingdon in 1601. He helped devise the institution of the title baronet as a means for King James I of England to raise funds. Despite his early period of goodwill with James I, during which he was made a baronet, Cotton's politics, based on his immersion in the documents, was essentially that "sacred obligation of the king to put his trust in parliaments" expressed in his published The Dangers wherein the Kingdom now standeth, and the Remedye (1628), which from the Court party's point-of-view was anti-royalist in nature; the authorities began to fear the uses being made of his library to support parliamentarian arguments: it was confiscated in 1630 and returned only after his death to his heirs. The Cottonian Library was the richest private collection of manuscripts ever amassed; of secular libraries it outranked the Royal library, the collections of the Inns of Court and the College of Arms; Cotton's house near the Palace of Westminster became the meeting-place of the Society of Antiquaries and of all the eminent scholars of England (DNB); it was eventually donated to the nation by Cotton's grandson and now resides at the British Library. The physical arrangement of Cotton's Library continues to be reflected in citations to manuscripts once in his possession. His library was housed in a room 26 feet (7.9 m) long by six feet wide filled with bookpresses, each with the bust of a figure from classical antiquity on top. Counterclockwise, these are catalogued as Julius (i.e., Julius Caesar), Augustus, Cleopatra, Faustina, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, Nero, Galba, Otho, Vitellius, Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian. (Domitian had only one shelf, perhaps because it was over the door.) Manuscripts are now designated by library, bookpress, and number: for example, the manuscript of Beowulf is designated Cotton Vitellius A.xv, and the manuscript of Pearl is Cotton Nero A.x. RobertCotton1626.jpg Robert Cotton http //en wikipedia org/wiki/Image RobertCotton1626 jpg c 1626 painting upper left text upper right text upper left coat of arms upper right coat of arms attributed to object history provenanceEvent 1626 commission Der Urheber des Bildes ist schon mehr als 70 Jahre tot - The author of the picture is already dead more than 70 years - L'auteur de l'image est mort plus de 70 ans PD-old-100 Cornelis Janssens van Ceulen 1620s portrait paintings 17th-century portraits with coat of arms Robert Bruce Cotton Sir Robert Bruce Cotton, 1st Baronet (22 January 1570/1 – 6 May 1631) was an English politician, founder of the famous Cotton library. He was of a Huntingdonshire parentage and educated at Westminster School, where he became interested in antiquarian studies under William Camden, and Jesus College, Cambridge (B.A. 1585).[1] Starting with his antiquarian notes on the local history of Huntingdonshire, he began to amass a library, in which the documents rivalled, then surpassed the official Public Record Office collections. He entered the Parliament of England as a member for Huntingdon in 1601. He helped devise the institution of the title baronet as a means for King James I of England to raise funds. Despite his early period of goodwill with James I, during which he was made a baronet, Cotton's politics, based on his immersion in the documents, was essentially that "sacred obligation of the king to put his trust in parliaments" expressed in his published The Dangers wherein the Kingdom now standeth, and the Remedye (1628), which from the Court party's point-of-view was anti-royalist in nature; the authorities began to fear the uses being made of his library to support parliamentarian arguments: it was confiscated in 1630 and returned only after his death to his heirs. The Cottonian Library was the richest private collection of manuscripts ever amassed; of secular libraries it outranked the Royal library, the collections of the Inns of Court and the College of Arms; Cotton's house near the Palace of Westminster became the meeting-place of the Society of Antiquaries and of all the eminent scholars of England (DNB); it was eventually donated to the nation by Cotton's grandson and now resides at the British Library. The physical arrangement of Cotton's Library continues to be reflected in citations to manuscripts once in his possession. His library was housed in a room 26 feet (7.9 m) long by six feet wide filled with bookpresses, each with the bust of a figure from classical antiquity on top. Counterclockwise, these are catalogued as Julius (i.e., Julius Caesar), Augustus, Cleopatra, Faustina, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, Nero, Galba, Otho, Vitellius, Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian. (Domitian had only one shelf, perhaps because it was over the door.) Manuscripts are now designated by library, bookpress, and number: for example, the manuscript of Beowulf is designated Cotton Vitellius A.xv, and the manuscript of Pearl is Cotton Nero A.x. | ||||